Sou Fujimoto is a renowned architect that has created one new space after another, embodying his own ideas and earning high praise both in Japan and abroad. In what was originally a building related to printing, we sat down with Mr. Fujimoto in his Shinjuku, Tokyo, office―a setting that hummed with an almost primitive atmosphere that seemed to suit the man well.

Reanalyzing Architecture from the Boundaries

When we talk about air conditioning, we are talking about making the air comfortable beyond the boundary separating the inside of a room from the outside. Mr. Fujimoto became fascinated with that boundary. Focusing on the many iterations of that boundary―between inside and out, or cities and houses―he set out to challenge himself with a wide variety of buildings. But where did this idea of the boundary being almost tangible originate?

"Our goal now and for the future is to build a comfortable space, so in our designs we ask ourselves if we are choosing the best method of doing so. This allows us to discover something new in the hopes of making the living space that much better. And through that analysis we find the inescapable idea of the division between the interior of a building and the outside world―from walls to glass windows. That's when I came to the conclusion that we must transcend those boundaries.

Rather than simply distinguishing the separation between inside and out, I began long ago looking into ways to enrich that connection instead. Of course, I drew influences from the ambiguous boundaries found in the traditions of Japan, including sliding doors that use paper and expansive gardens. Traditional Japanese architecture is largely non-existent today, but the different world we find ourselves in allows us to disconnect for a moment and see those traditions through a different lens. I find it interesting to consider how the people of bygone days thought and what that means for us today, and then what those ideas could look like if we could modernize them."

The Unexpected Connection between Urban Life and Nature

Mr. Fujimoto's project features many unique ideas that can be best perceived from the viewpoint of the boundary between the city and nature.

"I'm from Hokkaido―the countryside, specifically―so we had no choice but to create a strict division between inside and outside. When I moved to Tokyo, however, I found that the difference in inside and outside temperatures was not that extreme. Even when we go outside we are faced with man-made structures, so there are no sudden extreme changes from natural spaces to artificial spaces. I was intrigued by the idea of the inside and outside of buildings being gently connected.

When I opened the door of my roughly 11-meter-square one-room studio, I had to go through a narrow shared hallway to the road, which was also narrow. At only about 2 meters wide, the outside was even narrower than my room. It was interesting how the difference between being inside and being outside was not so easily distinguishable to the senses. But more than inside vs. outside, I felt that the difference between the architectural space and the urban space could be continuously traced.

Looking back even further to Hokkaido, where I had just moved from, I realized that I had unconsciously formed a strict boundary between the natural settings and man-made structures. And so I started to think of ways I could somehow connect these ideas.

From the physically busy spaces composed of natural forests that I played in as a child to the physically busy spaces composed of man-made structures that make up Tokyo―I became excited with the idea of different meanings of comfort that each place assumed. I also found it exciting that we could look at the boundary between the natural and the artificial as completely different from the boundary between inside and outside."

Architecture Born from Overlaps and the Thickness of Air

Armed with this focus on the exciting opportunities of boundaries, Mr. Fujimoto infused his passion into his innovative structure, House NA (2007-2011). This building made a bold statement on the boundary separating furniture and architecture.

"Despite being located in a typical Tokyo residential area, when you're inside the house you feel an enveloping softness, even though the building is made entirely of geometric structures. It's a very strange impression. The house is small, but it feels much wider. The various spaces overlap each other, and because they are not all visible the range is limited, but there are numerous overlapping spaces that allow you to sense the other side. I like to think that it is a construction reminiscent of Tokyo itself."

© IWAN BAAN

Before House NA, Mr. Fujimoto also completed House N (2006-2008), which could be defined as a house that questions the boundary between traditional Japanese architecture and more modern styles.

"With House N, I set out to create a structure based solely on the boundary. I blurred the lines between the inside and outside until they were unrecognizable. Although it was nothing like making a paper sliding screen, we stacked layer upon layer and kept going, all the while conscious of the fact that doing away with one boundary only opened the door to the next.

There is of course a structural boundary, but the thickness of the air itself is what actually creates the boundary with the outside. Where the inside air ends and the outside air begins changes slightly depending on the weather or the mood, such as how open-minded you feel like being at the time or if you simply want a quiet moment to yourself.

Within myself, I felt like I was creating this structure using the air itself. However, we can't do anything with just the air alone, so I focused on allowing the thickness of the air and the overlapping spaces to be felt in an effort to bring a feeling of openness and territory."

© IWAN BAAN

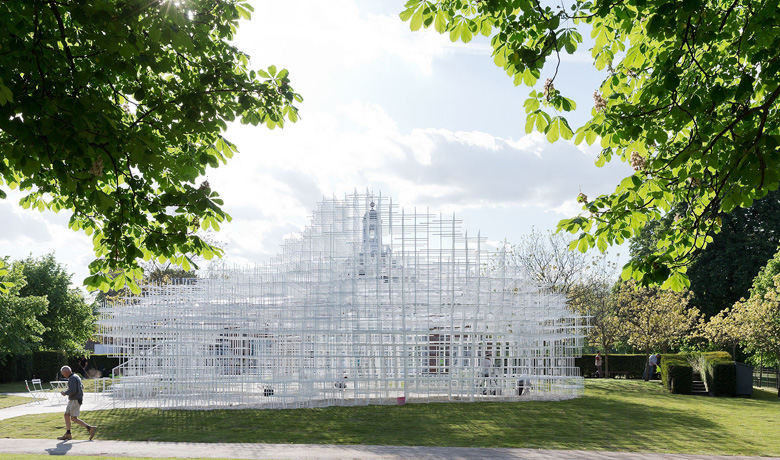

"This structure is a park pavilion built at the request of London's Serpentine Gallery in 2013. Actually constructed out of steel, the structure looks like a cloud made of piled up blocks of air. It's a mystical piece of architecture where changing the perspective just a little causes every overlapping space to change as well. Park-goers can relax and have a drink while enjoying the pavilion, sit in various locations within the pavilion, or simply walk around it. From afar, those within the pavilion will look as if they are floating along on a drifting cloud. It makes for a very moving sight."

© IWAN BAAN

What is True Comfort?

In looking at Mr. Fujimoto's projects, we begin to see a variety of forms of comfort itself accenting the various architectural styles.

"Even if something is defined as the ultimate state of comfort, each person has their own definition of comfort that depends largely on their mood. Sometimes hot weather is relaxing, and other times the freezing cold is nice. Sometimes sunlight weaving through the limbs of a tree is enjoyable, and other times being underneath the scorching sun is more enjoyable. This means that there is no absolute definition of comfort that applies to everyone. I think true comfort can only be discovered by following the senses and letting the choice come naturally.

This is why I try to avoid creating architecture that is too intrusive. My goal is to create depth and diversity that allow for various types of comfort and lifestyles."

The Unwavering Underlying Element

"One of my current projects is a multi-family house in France. The main element is an ordinary condominium, but the outer wall features numerous balconies. The building is located in Southern France, so the outside can be enjoyed to the fullest extent."

© SFA+NLA+OXO+RSI

"Next is this music hall being built in Budapest, Hungary. Located within a park, this structure is a large roof placed over a forest of trees. As the structure gradually becomes part of the forest, those under the roof will realize the shape resembles a music hall. The first floor will be completely transparent through the use of glass, and the trees will reach up and through the holes in the roof, which allow sunshine in even to what is actually an indoor space. This will also be a place where the boundary between the natural and the artificial begins to blur."

© Sou Fujimoto Architects

Despite employing various building methods in the creation of his innovative and revolutionary eye-catching buildings, Mr. Fujimoto seems always to incorporate the basic idea of boundaries into his work.

"I never feel that I need to express my own personality or my own roots into my architecture. Nevertheless, when judging the value of my designs, I constantly ask myself whether I am properly rooted in the design. So, even if the appearance is different, I find that the building is in some way connected to the underlying elements that make me who I am."