Kenichiro Mogi applies his broad perspective rooted in deep neuroscientific knowledge to a wide range of activities. In this interview, we asked Dr. Mogi, who is also well-versed in and passionate about the subject of creativity, about the relationship between creativity and air, and about what is required of today’s creators.

Ideas and inspiration result from endless combinations

As soon as he walked casually into the small, bare interview room, Dr. Mogi pulled out a rolled-up jacket from a heavy-looking backpack, and slipped it over the T-shirt he was wearing, all in one, swift movement. As if a switch had been turned on, his presence seemed to bring crispness to the hot, muggy atmosphere. First and foremost, we asked him where creative ideas and inspiration came from.

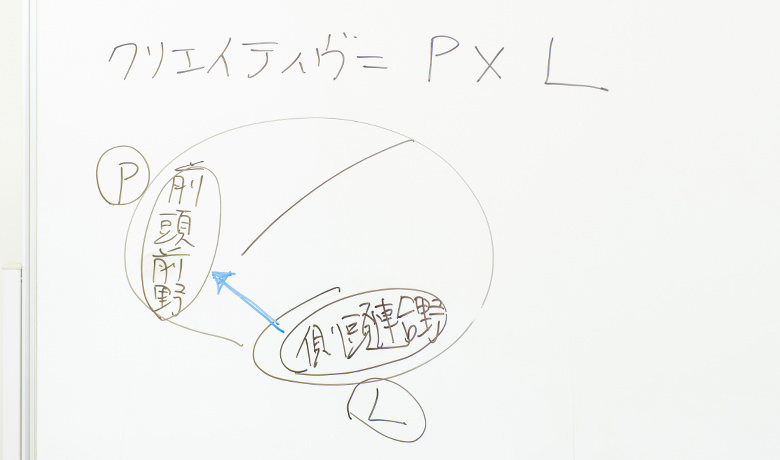

“That is one of neuroscience’s most fundamental queries. Whenever in need of an idea or inspiration, the brain’s frontal lobe looks inside the brain’s memory archive, called the temporal association cortex, for a new combination suitable for the given purpose or context. In the sense that they are retrieved from the temporal association cortex, ideas are not unlike memories. Whereas remembering involves retrieving past information as it is, however, ideas and inspiration are retrieved in combinations adapted to present needs. In this sense, they are not born out of nothing. It is a common illusion that ideas and inspiration arise from a void; they are always retrieved by the brain from endless combinations of the archived past.”

Hokusai’s masterpiece and his frequent moves

“A highly creative mind is subject to two conditions: One is a temporal association cortex richly stocked with experience. The more experienced you are, the better. The other is a frontal lobe capable of successfully retrieving from the pool. As a rule, the younger you are the better because the process requires enthusiasm and unconventional thinking. If you imagine the correlation as a graph, the temporal association cortex improves in proportion to experience, while the frontal lobe’s capacity to draw ideas and inspiration declines in proportion to experience.

This means, you are unbeatable if you are experienced, enthusiastic, and unconventional. An example is artist and printmaker Katsushika Hokusai, who is thought to have been in his seventies when he created his renowned Great Wave off the Coast of Kanagawa, which arguably remains one of the most internationally appreciated images originating in Japan. Hokusai probably had a well-stocked temporal association cortex, as well as an indefatigable spirit.

A detail of his life that seems to back this up is his frequent relocations. It is said that Hokusai moved houses more than 90 times in his life, which may have contributed to his creativity because, while it is often difficult to remain creative once we establish our career and settle down, relocating can compel us to adopt fresh perspectives. Perhaps we should all move more!”

Computer-generated image inspired by The Great Wave off the Coast of Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai

A genius as someone who can “read the air”

After agreeing that associating Hokusai’s house moves with his Great Wave is just the kind of thinking that makes Dr. Mogi unique, we went on to ask him about qualities essential for a creator. How does a creator remain creative?

“A creative genius of a given time is the product of a social milieu. Mozart, for instance, might not be an outstanding musical talent had he lived today. Likewise, there is no guarantee that Einstein would be a brilliant AI scientist today. A genius emerges when a person becomes the hub of a certain network in a certain society. Being at the right place at the right time is part of a person’s gift. My idea of a genius is someone who can ‘read the air,’ which means reading social situations.

Creative activities are inseparable from reading the mood and context of the times. The ability to inhale and exhale energetically is the mark of an outstanding mind because it means he or she knows who populates the network or society, and what they want at the present time. For this reason, good creators must also be good communicators, although this is not always easy.”

Value arising from a mood in the air

“The characters and feelings we associate with things are referred to as ‘qualia’ by people who work in my field. Qualia are the brain’s equivalent of data compression, akin to making a concentrated, undiluted solution of something. Famous, outstanding creators are the ones who make the concentrates. Many of us can dilute them, but are seldom capable of making the concentrates ourselves.

How can we become the ones who make the concentrates, then? Spotlighted as a possible clue is an unfocused, relaxed state of the brain known as the ‘default mode network.’ Data compression in the brain occurs only when the brain is relaxed and idle. I can say from my own experience of meeting talented creators that despite leading what I presume to be a hectic life, they invariably have an ease about them that reminds me of elementary school children on their summer holiday!

By the way, reputations and rumors constituting a mood can sometimes provide insight into the true nature of something. Acclaimed creators are often preceded by reputation, though not everybody really knows what the reputation is grounded in. I still feel, however, that reputation more often than not represents substance. Reputation rarely exists without substance. In a funny way, reputation arises only when a person possesses a quality people want to talk about. So, perhaps an outstanding creator is somebody who is equipped with such qualities. Again, mood is key to the value of an outstanding creator.”

The ultimate air conditioning

The final part of the conversation turned to real, physical air, as opposed to a mood or feeling in the air, discovering in the course that air, in fact, shared similarities with creative work.

“A comfortable indoor air environment is a very complex issue. I learned from hoteliers when I had the opportunity to do a report on several Tokyo hotels that admitting outside air into the rooms was often very important for overseas guests. Whether it was because of the fluctuation, or the freshness, it appeared that overseas guests found natural air desirable, even when the room was perfectly air conditioned. Perhaps there is a psychological element to the desire as well.

I also learned from a bespoke shoemaker that the best of shoes are so comfortable that many people prefer to keep them on even during long-haul flights. So, perhaps the ultimate air conditioning is something that perfectly mimics a gentle, natural breeze, comfortable enough to remove the need to open the window. If in the future space travel becomes commonplace, how well spaceships and space hotels can provide comfortable indoor air would become a vital issue that would have a great psychological impact on crew members enduring travel in spaces with only non-opening windows.

Each person has a different idea of comfort, and to add from a neuroscientific point of view, fluctuation is essential for keeping the brain, which loves variation, pleased. This is why powerful air conditioning on a hot day feels great the moment we enter the room, but starts to feel uncomfortable if we stay in the room for too long. Come to think about it, air is very much like creative work.”

In the sense that viewer and user reaction to creative works and products vary, and that our reaction to creative works changes with time, sometimes for the worse, creative work may be like air, or perhaps air is like creative work. Led by Dr. Mogi, the conversation that took us to and from creativity and air proved highly enjoyable and stimulating.