While many people may be familiar with fashion and product photography, few know anything about the world of architectural photography in which buildings are the subject. We wondered what role does air and light play in the work of photographers capturing and expressing three-dimensional architectural space. We interviewed Shigeo Ogawa, an architectural photographer whose extensive body of work attracts many offers from world-renowned architects.

The relationship of architectural photography and mountain photography

Beautiful sunshine comes streaming down from the overhead bay windows in Ogawa’s studio located in downtown Tokyo. The first floor includes gallery space where we are welcomed by stunning black-and-white landscape photographs. Mainly consisting of magnificent volcanos and mountains, these photos were photographed on film by Ogawa while he was traveling around Japan in his university days. He later scanned, adjusted, and reprinted them. We asked him why he hung mountain photos in his studio, instead of building photos.

“Actually, when I was a university student, I had planned to be a mountain photographer. But I read in a book written by Yoshikazu Shirakawa, a famous mountain photographer I admire, that studying architectural photography helps improve the expression of mountain photographs. That’s why I started photographing architecture.

Architectural photography and mountain photography have many things in common, such as how to use light, how to create a sense of solid, and how to capture texture and distance in shooting. Upon seeing a mountain photograph I had taken around 40 years ago, some people even said that it resembles architecture. In addition, the subjects of both architecture and mountains are large objects. They don’t move but they do look differently depending on the light, weather, season, and time of day. Another thing they have in common is that photographers walk around them to find the best angle.”

Snow and rain create an atmosphere

In listening to Ogawa, my impression of architectural photography as a very unique type of photography changes, and I discover its many similarities with mountain photography. When looking at mountain photographs, we can gain a strong sense of natural air. Can architectural photographs also create a similar feeling of air?

“It’s true that when we shoot buildings at work, we are often asked to capture bright light shining toward a building on a sunny day. Clear sky and bright sunlight cast strong shadows and create a sense of crispness. From my considerable experience in photographing Ando Tadao’s architecture, a sunny sky is imperative to capturing his concrete buildings. The contrast of light and shadow emphasizes the strength of concrete.

However, these conditions are not always required. At times, falling snow and rain make buildings very attractive in places filled with nature. This is a photo of Iwamizawa Station Complex in Hokkaido, with which I won the 2009 Good Design Award. I was thrilled that the beautiful flakes of falling snow in this winter landscape were clearly captured in the photo. The next photo was taken at the same square in front of the station just 30 minutes later. The change of weather is astonishing. Just the appearance of snow creates a special atmosphere from within the landscape.”

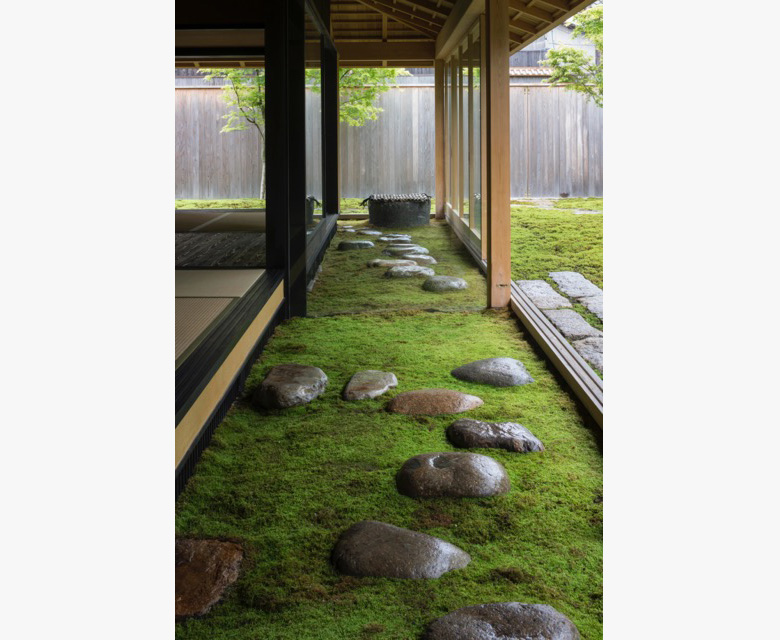

“Not only snow, rain and moisture in the air also create atmosphere. This photo shows beautiful moss extending into the house. This is a work of Hiroshi Sambuichi, an architect focusing on creating a better air environment using natural energy. He renovated a house in Naoshima, Kagawa, and added garden moss even to the inside of the house like a carpet. I took this photo on a rainy day, holding an umbrella, so you could feel a sense of wetness from this photo.”

What is vital to great photographs

“Whether or not architectural photography needs to include people is an important theme. I don’t really like including people in my work because the impact of models is so large that audiences pay more attention to the models than to the architecture. I’d rather use staffage figures that are melted unobtrusively into the background. I mull over the composition and light to show a hint of people without their presence.

For example, cushions are intentionally left unarranged to imply someone was sitting there, and reading glasses are casually put on a table, presumably by an occupant. These things make audiences feel like the people have gone but have left behind the air that they shaped.

I think great photos stimulate audience’s imagination. Photos with people provide only a single point of view. When including people in a photo, it’s important to make audiences feel time before and after the moment. The key is expressing air that lingers in the space by suggesting a hint of people and a story behind the photo.”

While listening to his words, I recognized my impression of architectural photography has greatly changed. Air and atmosphere are subtly concealed behind his organized, endlessly elaborate photographs that capture three-dimensional space. His work makes us want to go there and put ourselves in that place. “The most important thing in architectural photography is to make audiences feel like going to the place,” said Ogawa, with a smile.