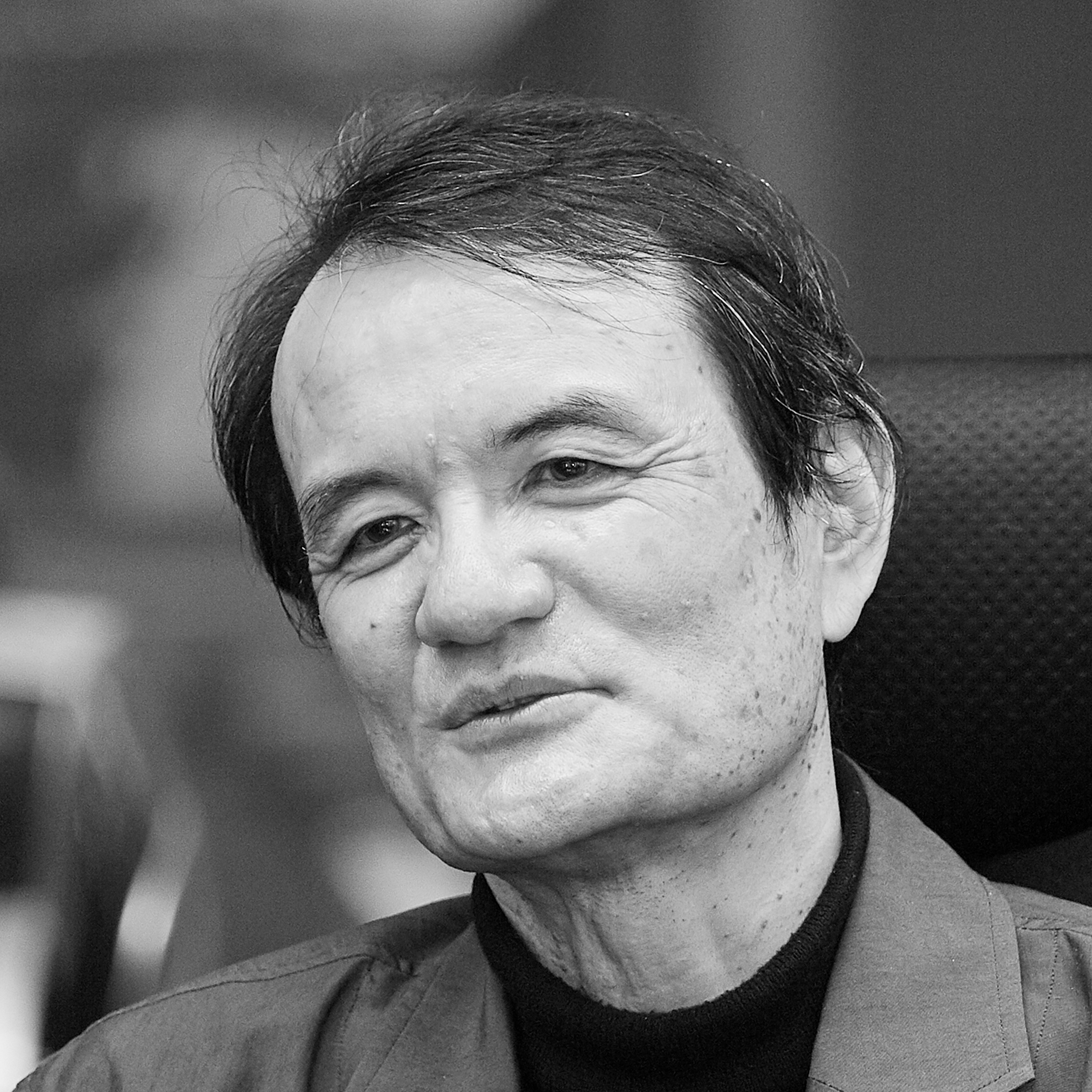

From daily necessities including watches and cooking utensils to automobiles, railroad cars, and even prosthetic legs that effectively incorporate cutting-edge technology for use in robots and by para-athletes, the ubiquitous designs of Professor Yamanaka span all categories of genres. Likewise, the Institute of Industrial Science at The University of Tokyo has been further expanding the design field by using prototyping to socialize the latest technology under research. We asked Professor Yamanaka, who has become renowned for not only his product designs but also for his keen acumen in observing various phenomena, what is required of modern designers.

Integration of knowledge in designs

Professor Yamanaka, at the beginning of your book on design ("Skeletal Structure of Design" Nikkei Business Publications, Inc.), you write, "When designing, you start first with 'seeing' and 'hearing.'" What do mean by that?

Yamanaka:

Creating something requires thinking of new combinations. So, the best method for generating the hottest idea is to combine fresh ideas that you have recently seen and heard with the knowledge that you already possess. After all, nothing originates from nothing. From this understanding, input, namely “what you see” and “what you hear,” becomes extremely important.

Anyone involved in design understands that it is the work of integrating diverse knowledge. Accomplishing that requires identifying the optimal combination from within an enormous amount of knowledge that includes not only the design object, but also the user, the social situation surrounding the design, production technology, and the workstyle of the worker. Often these will conflict with each other and can lead to a seemingly hopeless impasse. Nevertheless, when you see and hear many topics, there will be that moment when an idea suddenly emerges that utilizes both what you have seen and what you have heard. To reach that point, we must obviously expose ourselves to various types of knowledge.

When designing a new item, I talk to the engineer who will create it, tour the factory where it will be manufactured, go into town to see how it will be used, and visit the people who will use it. As I repeatedly perform fieldwork for peripheral information, there are some areas of gridlock and some areas of progress. I find that discovering the obscure combinations that are not what everyone considers “the normal approach” is especially useful. To uncover the hidden inconveniences and identify that which is truly desired, I think it’s important for you to encounter many aspects outside the norm while ensuring that the project maintains a constant presence in your mind.

Historically, observing from a scientific eye was the same as observing artistically from the eye of an artist. In the time of Leonardo da Vinci, many people were simultaneously artists, scientists, and even engineers. At some point, people became specialists and began seeing from their own specialized viewpoint, but designers are now asked to see from a variety of perspectives. That’s why it is so important to always be interested in things other than what you design.

Having curiosity as a motivating force

In addition to seeing and hearing, you place importance on another aspect: “Acting on the basis of curiosity.” Could you elaborate on that?

Yamanaka:

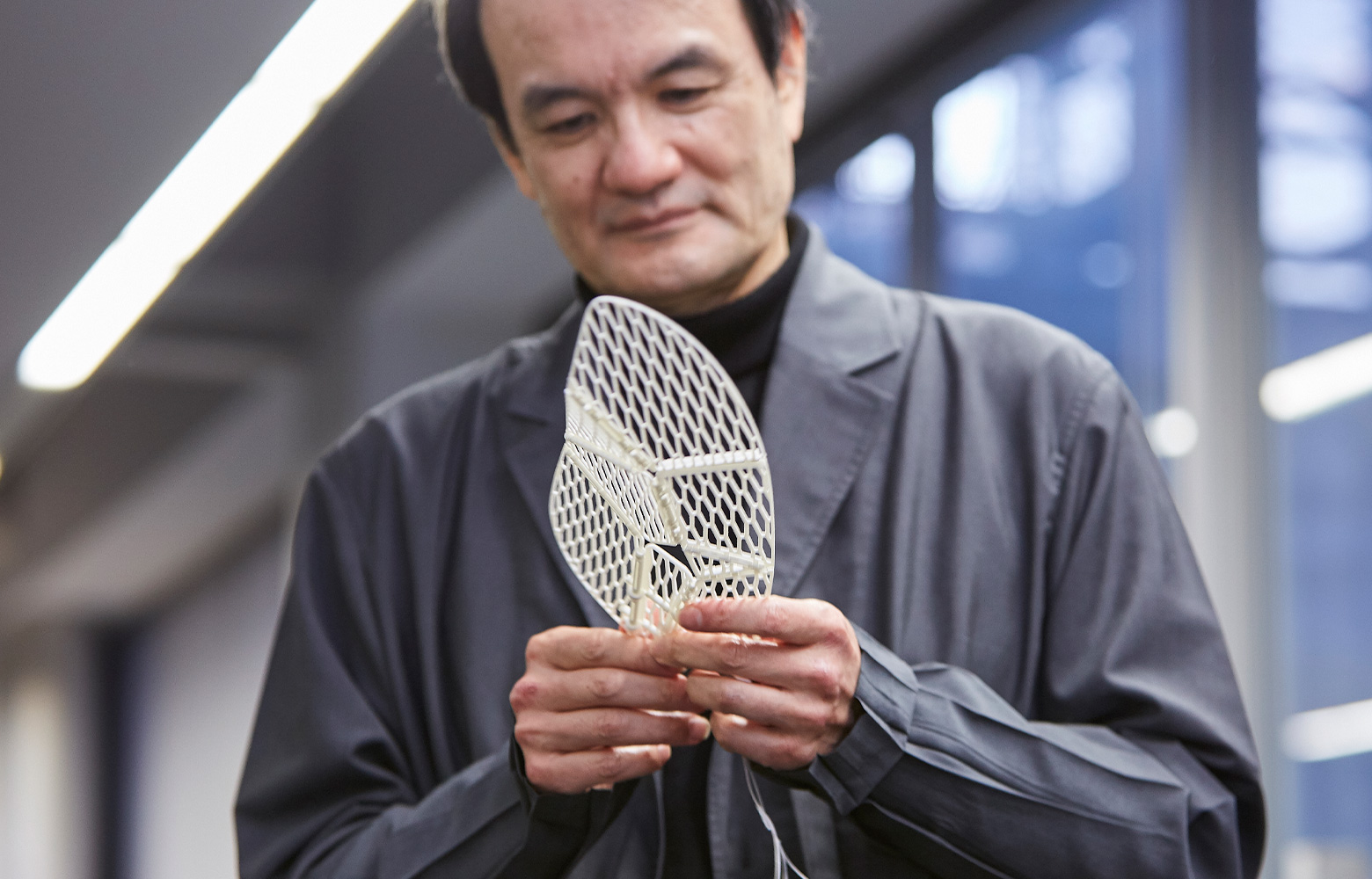

Recently, much of my work has been with prosthetic legs. Because this work involves thinking about a part of the human body, I have naturally learned much about legs and living things. On the other hand, I’ve also had a deep interest in a machine called the 3D printer, which is completely unrelated to that. Through this interest, it suddenly occurred to me, “Living creatures cannot be assembled and made.” To manufacture a product, we process parts from various materials one by one, bring them together, and ultimately assembly the parts. However, organisms are created by the gradual increase of cells into one body having complex functions and a delicate structure. Being aware of this, I realized that a 3D printer that could complete an object by the accumulation of layers one by one might be closer to the biological method than the manufacturing method that uses conventional processing machines. Assuming it were possible, making a prosthesis with a 3D printer would make perfect sense since it becomes part of the human body.

Yet this idea didn’t originate and evolve in the order beginning with “What type of technology is necessary to make prosthetic legs?” It began with curiosity that thought “3D printers are exciting,” and the experience of being involved with prosthetic legs led to the idea that “Maybe these two are compatible.” The timing of this is extremely important. Only seeking the knowledge that you think is needed actually limits the chances of encountering an unexpected idea. Not only is expertise in a certain field important, but it is also important to have curiosity apart from that field as a motivating force to act widely.

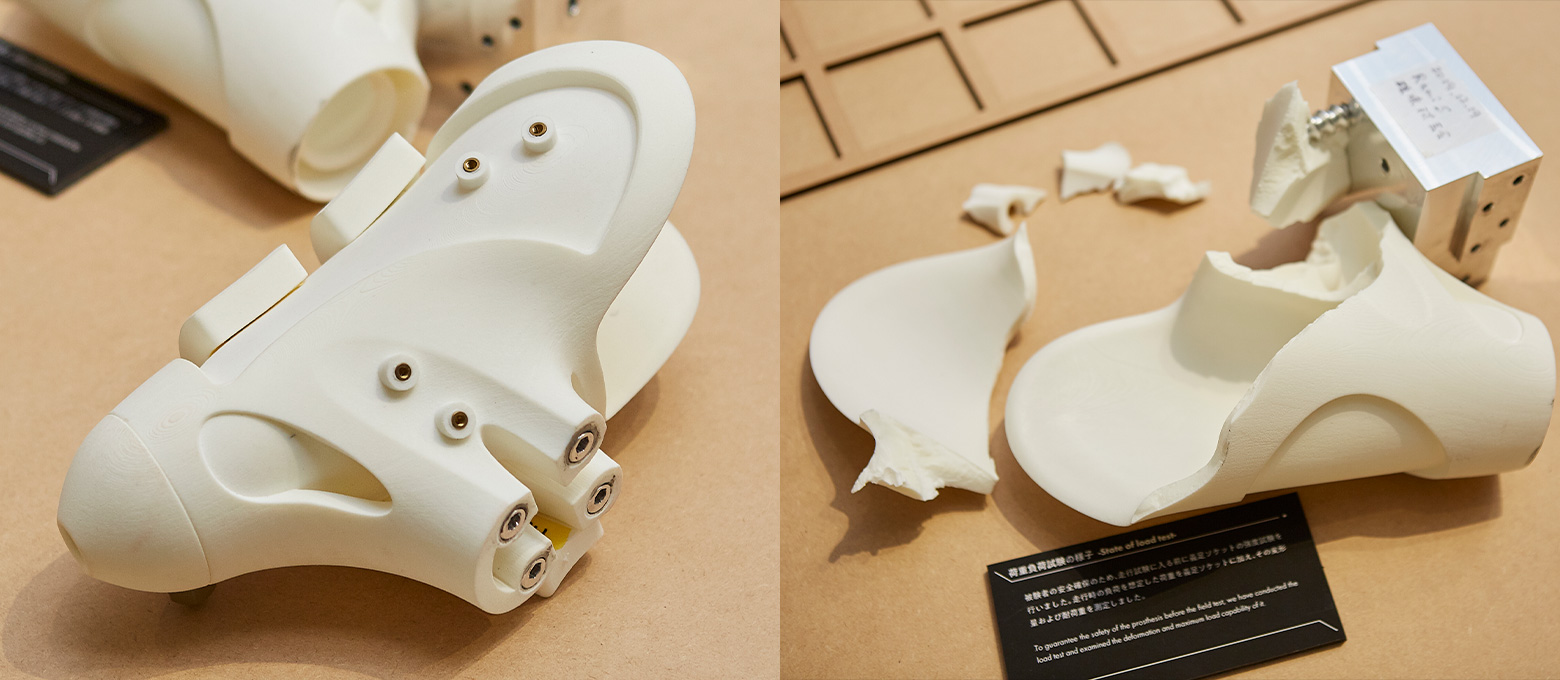

Verification sample by 3D printer

Left: Design for center of gravity position

Right: Aspect of load testing

Delaying the question of “Is it useful or not?”

Professor Yamanaka acts on the basis of curiosity that finds something “exciting” and says that he also values prototyping, which is one pillar of his research.

Yamanaka:

Prototyping is basically a “prototype of future life.” When ideas generated by a scientist enthralled in the excitement of a new technology or discovery take shape, we gain a glimpse of life in the future. Still, whenever I think that a new technology is exciting, I try to put off asking myself, “What is it useful for?”

For example, when you ask researchers in robotics, “What is a robot useful for?”, they will answer something like, “It will support life in the future,” “It is a robot useful for caregiving,” or “It can even be used for rescue.” However, there is no reason for a researcher to create a robot: there is only the pure sensation that creating movements mimicking humans is exciting. When speaking honestly of their true intent, all researchers will admit as much, and I don’t think that they should ignore that feeling and aim for something useful instead. What excites you? What makes you think: “Wow, it’s humanlike.”? If you think carefully about it, having the robot resemble the shape of a human being is unimportant. Instead, there will be moments with a gesture or reaction when you think, “Wow, it’s just like a human being!” The design is based on the desire to determine its true identity.

Robots that react to humans

In 2019, the research laboratory of Professor Yamanaka held the Zowa-Zowa Exhibition that pursued that feeling of excitement. Here robots that moved a little unexpectedly were lined up together.

Yamanaka:

The robots reacted to viewers with shifting, springy, and fluffy movements. Only those movements that we associate with “living creatures” were extracted for the created objects. The reason we created that type of robot was that when we as human beings communicate with other living creatures we draw conclusions from various non-verbal information and think, “It looks busy,” “It is interested in me,” “It understands (or doesn’t understand) this,” or “It seems bored.”

Building robots tends to be command-based, but it is actually much more important to have communication that isn’t. Designing an artifact to react in this way results in communication that is different from sending commands by a remote controller. It has the potential to be one of the most important parts of communication between an intelligent machine and human beings.

From immersion in the "excitement" of technology

If I were asked regarding the robots for Zowa-Zowa Exhibition, “What are they useful for?” the explanation would be something like: “We are searching for a key component to robot interfaces.” However, that answer is more of an after-the-fact justification. Wondering “What would be thrilling and exciting for a robot to do?” is closer to the truth, and I think that the point of not making a robot look like the real thing was confirmed to be correct.

In saying that, I think that I am partially touching upon a fundamental aspect. Is it okay to simply make a robot look human? Is it appropriate to attach eyes and a nose? Is having a smile on the LCD screen really how we want to communicate? That was the underlying theme of the mysterious robots of the “Zowa-Zowa” Exhibition. It is very important to start properly asking those questions, but this too can only be discovered on the basis of curiosity. I don’t think it’s an idea that emerges from a logical space of “Let’s be useful.”

While there are times when we start off something new by deciding a theme in advance, for example, using technology such as a 3D printer or biotechnology, we should first try to immerse ourselves in the excitement of that technology. And if we look 30 years into the future and retrace our steps from then to now, there are certainly many things that can be done today. I think it’s a good idea to start from a place that “looks exciting.”